I must have something to engross my thoughts, some object in life which will fill this vacuum, and prevent this sad wearing away of the heart.

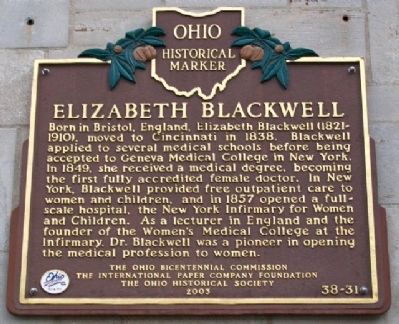

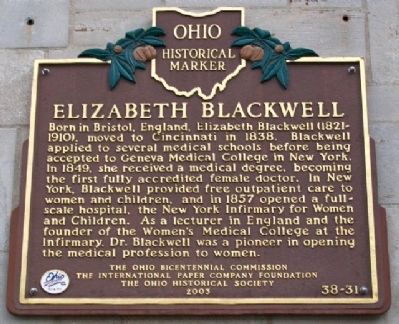

Continuing my three part series about Elizabeth Blackwell

, each covering one of the three main periods of her life -- her childhood and early education, her time in medical school and early career, and her professional life and efforts to improve educational opportunities for women.

+ + +

The idea to pursue medicine was first suggested to Elizabeth by a friend in Cincinnati who was dying of a painful disease (likely

uterine cancer), who believed a female physician would have made her treatment more comfortable.

At first, Elizabeth was repulsed by the idea of a medical career, but the more she tried to not think about it, the more the idea appealed to her. She consulted with various friends and physicians, to get their opinions.

The answers I received were curiously unanimous. They all replied to the effect that the idea was a good one, but that it was impossible to accomplish it; that there was no way of obtaining such an education for a woman; that the education required was long and expensive; that there were innumerable obstacles in the way of such a course; and that, in short, the idea, though a valuable one, was impossible of execution.

This verdict, however, no matter from how great an authority, was rather an encouragement than otherwise to a young and active person who needed an absorbing occupation.

Part of her decision to become a doctor was due to the fact that she desired to live her life independently, with no wish to get married.

I felt more determined than ever to become a physician, and thus place a strong barrier between me and all ordinary marriage. I must have something to engross my thoughts, some object in life which will fill this vacuum and prevent this sad wearing away of the heart.

But it wasn't as easy as she might had thought it would be. Although she had some friends who agreed to help her with the cost, it was not enough, and she needed to find further employment so she could save the money. This time, she took a teaching position in Asherville, North Carolina, and embarked on an eleven-day cross-country adventure via carriage.

I find interesting details of that long drive, when every day took me farther and farther away from all that I loved. We forded more than one rapid river, and climbed several chains of the Alleghanies in crossing through Kentucky and Tennessee into North Carolina. The wonderful view from the Gap of Clinch Mountain, looking down upon an ocean of mountain ridges spread out endlessly below us, and seen in the fresh light of an early morning, remains to this day as a wonderful panorama in memory.

In Asherville she stayed with Reverend John Dickson, who had been a physician before he became a clergyman. Dickson approved of her career aspirations, and gave her full use the medical books in his library to study. Although she faced doubts and loneliness, she soothed herself with prayer and religious contemplation. She also renewed her antislavery activities.

While she saved money, she also studied to improve her chances of being accepted into medical school. Sadly, a year after arriving in North Carolina, the school where she was teaching had to close. The then traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, to stay with the brother of Reverend Dickson, also a physician, as well as a professor at the local medical college.

In 1847, once she had saved up enough money, she moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she believed she would have the best opportunity to prove herself to the various medical schools in the area.

During the following months, whilst making applications to the different medical colleges of Philadelphia for admission as a regular student, I enlisted the services of my friends in the search for an Alma Mater. The interviews with the various professors, though disappointing, were often amusing.

That she found her experience to be "amusing" is remarkable. Her stories of having professors laugh in her face, or stare at her silently, denying her their recommendations, and all other manner of disappointing interactions, speaks more to her own sense of self-respect and her strong belief in herself. Many gave her the advice to travel to Paris or to impersonate a man to study medicine, but she refused to entertain either of those ideas.

But neither the advice to go to Paris nor the suggestion of disguise tempted me for a moment. It was to my mind a moral crusade on which I had entered, a course of justice and common sense, and it must be pursued in the light of day, and with public sanction, in order to accomplish its end.

While she was visiting various schools in the area, she studied privately, taking instruction on anatomy, visiting patients, and even attending lectures. After she'd exhausted the local colleges, she expanded her search to colleges in more rural areas. In October of 1847, she was accepted as a student at Geneva Medical College in New York. While all other programs had denied her outright for her sex, the faculty at Geneva put her acceptance to a vote by the male students of the class, with the understanding that if even one student objected, she would be turned away. The students unanimously voted to accept her, likely because they thought it was such a ridiculous event it was a joke.

Elizabeth quickly found her way around the campus, and her mere presence had a profound effect on the young men, turning them into well-behaved gentlemen. According to the faculty, before her arrival, there was so much confusion and chaos in the lecture hall that

the lecture was barely audible. But with Elizabeth in the class, the male students sat quietly and listened attentively to lecture.

At one point, the anatomy professor asked her to excuse herself from the class on reproduction, believing it would be too vulgar for her delicate mind. Instead, her eloquent response changed his mind, but also elevated the previously obscene nature of the lectures.

Today the Doctor read my note to the class. In this note I told him that I was there as a student with an earnest purpose, and as a student simply I should be regarded; that the study of anatomy was a most serious one, exciting profound reverence, and the suggestion to absent myself from any lectures seemed to me a grave mistake.

On the whole, Elizabeth worked well with both professors and students. But being the only female student, she experienced a sense of isolation as well. Certainly the townsfolk of Geneva thought her an oddity. In the interest of maintaining her respectability and focus, she rejected all advances made toward her, whether for courtship or simply friendship.

Had I been at leisure to seek social acquaintance, I might have been cordially welcomed. But my time was anxiously and engrossingly occupied with studies and the approaching examinations. I lived in my room and my college, and the outside world made little impression on me.

Between terms, she returned to Philadelphia, where stayed with Dr. Elder while she applied for positions which might offer her clinical experience. The city commission that ran Blockley Almshouse, the Guardians of the Poor, granted her permission to work there. After some initial skepticism about her abilities, she slowly gained acceptance among the majority of the staff, although some of the younger resident physicians still refused to assist her in diagnosing and treating her patients.

During my residence at Blockley, the medical head of the hospital, Dr. Benedict, was most kind and gave me every facility in his power. I had free entry to all the women's wards, and was soon on good terms with the nurses. But the young resident physicians, unlike their chief, were not friendly. When I walked into the wards they walked out. They ceased to write the diagnosis and treatment of patients on the card at the head of each bed, which had hitherto been the custom, thus throwing me entirely on my own resources for clinical study.

Despite the demonstrations of poor behavior, she gained valuable clinical experience. In particular, she was so appalled by the syphilitic ward and those afflicted with typhus, she wrote her graduating thesis at Geneva Medical College on the topic of typhus. The conclusion of her thesis showed a link between physical health and social stability, which would become an enduring

theme in her future work.

On 23 January 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to achieve a medical degree in the United States.

After the degree had been conferred on the others, I was called up alone to the platform. The President, in full academical costume, rose as I came on the stage, and, going through the usual formula of a short Latin address, presented me my diploma.

She returned to Philadelphia, but only stayed for a short time before receiving an invitation to join a cousin on a trip to England, and she took the opportunity to continue her studies in Europe. She visited hospitals in England, before heading to

Paris. No surprise, she was rejected from many hospitals because of her sex, but in others she found a warm welcome.

Mr. Parker, surgeon to the Queen's Hospital, had some difficulty in believing that it was not an ideal being that was spoken of; but when he found I was really and truly a living woman he sent me an invitation to witness the amputation he was going to perform, and promised to show me all the arrangements of the institution, sending also a note of admission to the college and museum.

In June, she was allowed to enroll at La Maternité, with the understanding that she would be treated as a student midwife instead of a physician. She enjoyed her time working with the other young women and received quite a bit of encouragement from her professors.

The poor woman whom I have attended as my first complete patient gave me a little prie-dieu which she had made. Her humble heart longs to express its gratitude. I put it in my Bible were my friends are reading today... M. Dubois again waited after the lecture to say a few pleasant words. He wished I would stay a year and gain the gold medal; said I should be the best obstetrician, male or female, in America!

Tragically, in 1849, while treating an infant with ophthalmia neonatorum, some of the solution spurted into her left eye and it became infected. She lost all sight in that eye, which ended her hope of becoming a surgeon. She took a couple of months to recover, and traveled a bit around Europe. In 1850, she returned to London to continue her studies at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, and attend lectures given by prominent surgeons and physicians of the era.

While she was busy working on her own studies, she stayed in touch with the social and political activities of her friends and family back home.

My great dream is of a grand moral reform society, a wide movement of women in this matter; the remedy to be sought in every sphere of life -- radical action -- not the foolish application of plasters, that has hitherto been the work of the so-called 'moral reform' societies; we must leave the present castaway, but redeem the rising generation.

She moved in the upper echelons of London society, meeting with Lady Byron and other rather famous people.

One of my most valued acquaintances was Miss Florence Nightingale, then a young lady at home, but chafing against the restrictions that crippled her active energies. Many an hour we spent by my fireside in Thavies Inn, or walking in the beautiful grounds of Embley, discussing the problem of the present and hopes of the future.

In 1851, she decided to return to the United States with the hope of establishing her own practice. She had difficulty gaining patients, but kept her spirits high, and continued to work to gain more attention in the media, and work to improve educational programs for girls and women. She had limited access to opportunities to further her own medical education, and so she focused her attention on speaking about medical issues such as hygiene and preventative medicine. In 1852, many of her lectures were published as

The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls, providing a valuable resource on the physical and mental development of girls.

I can't do the work of SRPS without your your support!

If you like what you read here, please share this post with your friends.